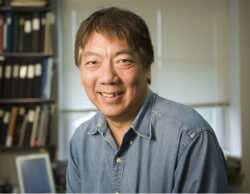

Steven Hsiao, World Leader in Sensory Physiology Research

Steven Hsiao, World Leader in Sensory Physiology Research, Has Died

Steven S. Hsiao, an internationally renowned researcher whose innovative experiments on how the brain perceives the shape, size and texture of three-dimensional objects could lead to the development of artificial limbs that can feel, died at The Johns Hopkins Hospital on June 16 of lung cancer. He was 59.

Steven S. Hsiao, an internationally renowned researcher whose innovative experiments on how the brain perceives the shape, size and texture of three-dimensional objects could lead to the development of artificial limbs that can feel, died at The Johns Hopkins Hospital on June 16 of lung cancer. He was 59.

“Steve has been a defining part of Hopkins brain science for over three decades,” says Ed Connor, a professor of neuroscience and director of The Johns Hopkins University’s Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute.

Hsiao’s work had both basic science implications for complex information processing in the brain and clinical applications for developing the technology to create artificial limbs that convey the impulses that would give amputees a sense of touch, Connor says.

A protégé of Vernon Mountcastle, the Johns Hopkins neuroscientist acknowledged as the founder of the field, and the late Kenneth Johnson, Hsiao became the foremost expert in how the brain processes the sense of touch and “played a major role in training the next generation of researchers” in the brain mechanisms of touch perception, Connor says.

As a prolific researcher, Hsiao wrote extensively. “Many of his papers are considered classics in the field,” says Richard Huganir, professor and director of the Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience at The Johns Hopkins University, where Hsiao had been a faculty member since 1992. He also held joint appointments in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. In addition, he served as scientific director of the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute, where he guided overall research, hiring and student affairs. The work within his lab was instrumental in maintaining Johns Hopkins’ role as a world leader in sensory physiology.

Hsiao’s research expanded “into many exciting directions,” Connor notes, including studies to determine how individuals possess the “remarkable ability to recognize objects with our hands alone”; how we maintain “tactile attention,” or the ability to focus on specific objects and ignore most touch information, such as pressure from chairs; how we perceive things that move across our skin; and “fine texture discrimination,” such as being able to tell silk from linen.

Born in Washington, D.C., the youngest of seven children, Hsiao obtained his bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering and his master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Duke University in 1976 and 1978, respectively. He briefly worked in private industry as a nuclear engineer, then served as a biomedical engineer at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) before entering the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he obtained his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering in 1990.

Following two years as a research fellow in biomedical engineering and neuroscience, Hsiao joined the Johns Hopkins faculty as an assistant professor of neuroscience. He was promoted to associate professor in 2000 and to full professor in 2007. He also was a chaired professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China, and served as co-director of Johns Hopkins’ neuroscience graduate program.

Since 1993, Hsiao’s research was supported continuously by NIH. He collaborated extensively with researchers inside and outside of Johns Hopkins and was extremely active in teaching medical students and postgraduate researchers.

Hsiao’s research concentrated on four aspects of tactile perception: spatial form, texture, vibration, and the mechanism and role of selective attention in processing physical sensation. Among the tools he and colleagues developed to advance his research is a 400-probe stimulator that can deliver any pattern of sensation to the skin to uncover the spatial and temporal processing properties of the neurons in the somatosensory cortex, the brain’s primary area for reacting to sensations from any part of the body besides the eyes and ears.

Outside of the lab, Hsiao was a devoted husband and father. He was a fan of Duke basketball, Orioles baseball and Ravens football, and he enjoyed sailing, fishing, cooking, tennis, basketball, fine wines and scotch.

“His easygoing, friendly personality made him a favorite among graduate students, and he was highly valued as a friend and collaborator by his faculty colleagues,” says Connor.

Hsiao is survived by his wife, Jocelyne DiRuggiero, an associate professor of biology at Johns Hopkins; sons Kevin, 17, and Andrew, 15; two brothers; and four sisters.

The family is having a private memorial service, and a university memorial symposium will be held in the fall.